read_more

See all projectsAn Amateur's Guide to Capturing the Northen Lights

Gear will be forgotten, weather will turn, and tripod parts will freeze off. And it'll still all be worth it... right guys?

When you think about it, a ridiculous sequence of cosmic events needs to fall into place for us to see the Northern Lights here on Earth as consistently as we have in the past few years.

It begins with our sun.

Every 11 years, the sun's magnetic poles flip. North becomes south, and vice versa. This pattern has been true for at least the several centuries that we've recorded sun spot numbers.

The sun's magnetic field flips and sunspot activity increases

Average daily number of sunspots, by year

(Side note, we don't know for sure why the sun's field reverses, but research suggests it could be because Earth, Venus, and Jupiter all align every 11 years and combine to influence the sun's magnetic field).

As aurora chasers, the best time is near a solar maximum - the peak of this eleven-year cycle, when the number of sun spots grows from nearly zero to hundreds.

We're on the tail end of a solar maximum

Average daily number of sunspots, by month

Some sun spots are more active than others, rotating with the sun into our view from Earth every 24 days. They’re also constantly appearing and fading. So once in a while, a particularly active sun spot might face our planet.

If we're lucky, an active sun spot - which is basically an unfathomably large, churning cauldron of intense magnetic fields 2,500 stronger than our own - must conjure a solar flare. These sudden electromagnetic pulses bursts can be over 100,000km long in X Class flares, which is the strongest category and occur more frequently during the solar maximum.

The largest solar flares erupt when there are more active sunspots

Irradience (a measure of strength) of the largest 1,000 solar flares since 1995.

These X Class flares usually produce coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which spew plasma, or charged particles like electrons and protons, into space. The stuff in these CMEs - if all else goes to plan - is what will eventually produce the aurora in our skies here on Earth.

CMEs hurl a stream of plasma into space, flowing through a solar wind with its own fluctuating magnetic field. As you’d expect, we hope to see particularly strong CMEs in order to have a chance of widespread aurora.

A CME bursts from an X-class (X2.0) flare in February 2025.

Captured by NOAA's GOES-19 instrument

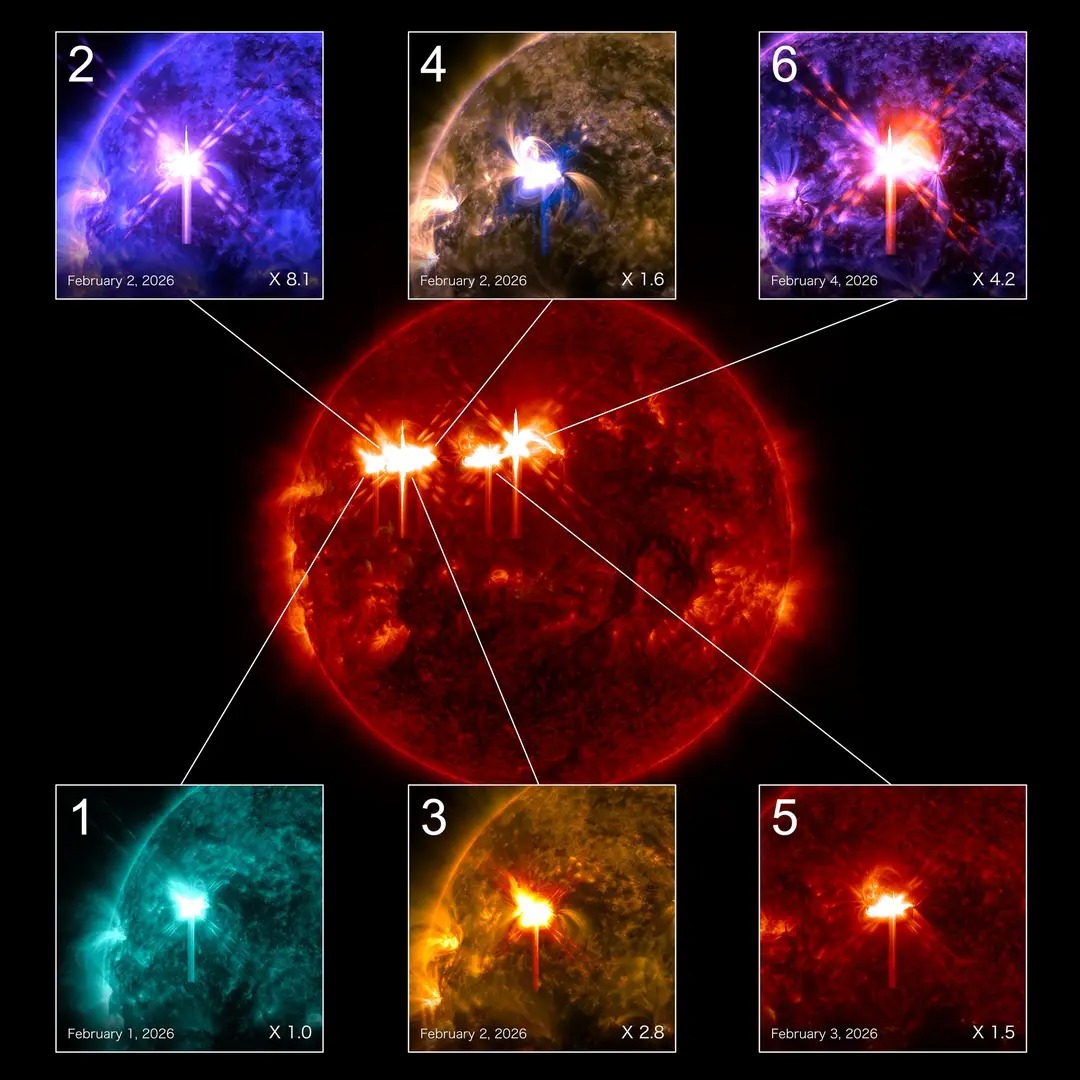

Large X-class flares are often associated with large CMEs, but not always. In early 2026, sunspot AR4366 passed across our view, spewing more than 5 X-flares and dozens of M-flares in a matter of days - one of the densest flare actions seen in decades. However, most of these flares were not accompanied by CMEs, disappointing many aurora chasers.

Sunspot AR4366 produced six intense X-flares, but no CMEs.

Captured by NOAA's Space Dynamics Observatory (SDO)

Unfortunately, not all sun spots emit solar flares and CMEs in Earth’s direction. We only have a chance at seeing the aurora if the CME faces our planet. Direct hits have the greatest aurora potential. Those flares in the image above were accompanied by some CMEs, but most of them weren't Earth-directed, and those that were only glanced us.

About half of 2025's 120+ CMEs missed our planet

Predicted strength of all recorded CMEs in 2025 (in Kp values)

Toggle between the Hit and Miss options in the chart above to see how fortunate we were that the strongest CMEs of 2025 also happened to be directed towards Earth

So to recap, to have even a chance at a good aurora storm, here's what needs to have happened so far:

- The sun is near its solar maximum

- An active sunspot faces our planet

- The sunspot releases a large solar flare

- A strong CME accompanies the flare

- The CME is directed towards Earth

Let's see what happens when the CME hits our planet.

It becomes a matter of attraction.

About one to five days after the Earth-directed CME leaves our star, it will collide into our atmosphere, causing a solar storm. These geomagnetic storms range in severity from minor (G1) to severe (G5). We encounter around four G5 storms every solar cycle (eleven years).

Solar storms increase the likelihood of seeing aurora in lower latitudes.

In higher latitudes like Alaska where this photo was captured, aurora can occur even without a solar storm.

To see a strong storm, the CME needs to be very fast and dense when it reaches us. Speeds of 900+ km/second with density over 50/60 particles per cm3 have been associated with some of this solar cycle's best aurora activity.

There’s yet one more crucial characteristic of the CME that influences if and where we’ll have aurora. The CME carries its own, ever-fluctuatic interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) as it hurtles through space. The orientation of that field once it hits Earth’s magnetic field is crucial.

If its north-south direction (known as Bz) is positive, much of the CME’s plasma cloud will repel around Earth’s own north-facing (positive) magnetic field. But if the Bz is negative, it will be sucked into ours, increasing the chances of widespread aurora.

When conditions are right, our magnetic fields attract the CME's particles into our atmosphere's

This animation shows how a CME strike entangles magnetic fields. (Via YouTube)

Just having negative Bz isn’t necessarily enough. The more negative it is, the better the likelihood of widespread aurora. -10nT (nanoTesla) is good, but strong storms can drop to -50 or even over -100 or further. (Most aurora photos in this post are from rare -200nT storms).

Once these conditions are in place, we are likely to be in the midst of a strong geomagnetic storm. If weather and other circumstances allow, an aurora glow will likely be visible at lower latitudes than usual.

Where exactly does that glow come from? When the charged particles from a CME are sucked into our atmosphere, they collide with gas atoms and "excite" them. To calm back down, the atoms release that extra energy as flashes of light called photons.

Aurora looks green when the particles strike oxygen in lower altitudes (60-150mi above us). Red hues appear when they hit oxygen in thinner, higher altitudes. Rarer purple colors occur when particles hit nitrogen in lower altitudes.

Finally, we encounter a substorm.

But most people don’t think of a gentle glow when they imagine aurora; they’re thinking of substorms: brief moments of intense activity, like the vivid colors and moving pillars of light you’ll see in this timelapse from a January 2026 G4 storm.

An aurora substorm in Alaska

This substorm occured after the aurora charged for over an hour.

In the field during a solar storm, aurora chasers read data from the GOES satellites to estimate when a substorm will occur. They’ll look for patterns of sudden disturbances in what would otherwise be a perfect “S” wave.

(I won’t try to explain why because The Aurora Guy does it so well here.)

Substorms occur with sudden surges after periods of charging

Z component of the magnetic field on October 5, 2024 (in nT)

At this stage, we introduce one final metric into the fold to help us understand if and where we are likely to see aurora: the planetary K-index, or Kp.

A measurement of the disturbances in Earth’s magnetic field, the Kp-index ranges from 1 to 9 and is estimated every three hours. It’s used as a rough indication of the intensity and visibility of aurora. Kp values below 3 suggest low activity, with faint visibility near our poles. Kp values of 6-9 suggest high activity, with visibility reaching toward medium and low latitudes.

Sustained high Kp reflects active aurora at lower latitudes

Kp index for 8 days, every three hours

In general, Kp values aren't that helpful for trying to predict aurora. But they are a useful way to describe its visibility at different latitudes. These maps show how different Kp values relate to visibility:

If in the best case scenario we find ourselves amidst a G3 to G5 storm, with Kp values of 6-9, we are likely to have aurora at lower latitudes.

The final boss: A trifecta of obstacles

At this stage, an absurd sequence of cosmic events has aligned for us to have a shot at seeing aurora in lower latitudes:

- The sun is near its solar maximum

- An active sunspot faces our planet

- The sunspot releases a large solar flare

- A strong CME accompanies the flare

- The CME is directed towards Earth

- The CME is moving at high speed when it hits Earth

- The CME is dense when it hits Earth

- The CME's Bz component is negative when it hits Earth

Three final pieces of the puzzle stand in our way now:

- Clouds: You need clear skies - at least in the direction of the sky where the aurora is likely to appear: towards the north/south horizon or overhead, depending on your latitude and the Kp estimates.

- Light pollution: You should find dark skies with low light pollution, at times when the moon won’t be up.

- Daytime: Aurora can be ablaze above you, but washed out by the light of day. Fortunately, larger storms can endure for long enough for them to be seen once night falls across hemispheres.

Aurora chasers track weather, light pollution, and sun/moon patterns to help battle these final obstacles.

The aurora is never guaranteed, requiring a near-impossible string of cosmic victories just to reach our eyes. But when those conditions finally click, the result is a fleeting masterpiece that makes the wait entirely worth it.

Aurora over Mt. Hood, Oregon

This substorm occured after the aurora charged between 11p-2am.